NOTE: This article features music tracks auto-generated by YouTube which might not be viewable outside of the U.S.A.

Anybody can make up monsters, but the ones that stick in the culture, folklore in the past and now most commonly in specific media, usually strike a chord deep within the human consciousness. If people learned anything from pop psychology in the 70's it was that folklore persists because of psychological and emotional parallels between folklore and human needs and anxieties - "Little Red Riding Hood" can be interpreted as a warning for girls to stay away from predatory men, to quote a famous extrapolation by the likes Bruno Bettelheim's The Uses of Enchantment, the parent text to most theories of this sort, and Angela Carter's story "The Company of Wolves" from her collection The Bloody Chamber. The latter was adapted into a rapturously insane film by Neil Jordan (co-writing the screenplay alongside Carter herself), a good sign that there's a great deal of appeal in this most haunting version of the story. In some ways these connections we create with fiction and (supposed) fact are obvious if one is able to slip into the mindset of those who can't speak directly of what lies beneath the surface of life. However, some folk tales are so vivid, so creative and so off-the-wall that they defy easy explanation, owing more to pure art than subconscious messages, and that's where Baba Yaga sprints in on giant chicken legs.

Anybody can make up monsters, but the ones that stick in the culture, folklore in the past and now most commonly in specific media, usually strike a chord deep within the human consciousness. If people learned anything from pop psychology in the 70's it was that folklore persists because of psychological and emotional parallels between folklore and human needs and anxieties - "Little Red Riding Hood" can be interpreted as a warning for girls to stay away from predatory men, to quote a famous extrapolation by the likes Bruno Bettelheim's The Uses of Enchantment, the parent text to most theories of this sort, and Angela Carter's story "The Company of Wolves" from her collection The Bloody Chamber. The latter was adapted into a rapturously insane film by Neil Jordan (co-writing the screenplay alongside Carter herself), a good sign that there's a great deal of appeal in this most haunting version of the story. In some ways these connections we create with fiction and (supposed) fact are obvious if one is able to slip into the mindset of those who can't speak directly of what lies beneath the surface of life. However, some folk tales are so vivid, so creative and so off-the-wall that they defy easy explanation, owing more to pure art than subconscious messages, and that's where Baba Yaga sprints in on giant chicken legs.

Arguably the most famous of all Slavic folk characters, Baba Yaga, and her hut, stand tall as crowning achievements of weird storytelling. Depicted by herself or as one of three identically-named sisters, Baba Yaga has many characteristics of a classic witch - she's an old woman with an iron will and magical powers, powers which she often uses to evil and destructive ends. However, the tools she uses to wield those powers are unique - a mortar and pestle used to fly around, and a hut that stands on huge chicken legs - and her tales often let her help those in need. Her first known appearance on record even noted her uniqueness in the Slavic pantheon, equating many of the other gods to the Roman pantheon but recognizing her singular existence in the culture. Another interesting ability is the occasional skill of sniffing out the "Russianness" of people who visit her, much like the scent of the blood of an Englishman if you ask me. Her domain is the depths of the forest, and if I had to paint her in symbolic terms I'd burrow into that woodsy connection pretty deep. Forests have long been sources of conflicting experience for humankind, teeming with life and potential food and safety but forbidding in their density and lurking dangers; Baba Yaga's personality, alternately helpful and wrathful, fits with this pretty snugly. The good news is that you don't have to take just my word for it, as there are a ton of adaptations and portraits of the Grand Crone to choose from, a heap of which we're talking about today.

Late Romantic and early modern Russian composers were many things, firstly excellent, but also way into capturing the Russian identity in their music, both abstractly and programmatically. The latter method brought a heck of a lot of identity into musical form, from the landscape (such as Borodin's In the Steppes of Central Asia) and climate (such as Tchaikovsky's The Seasons) to stories both literary (such as Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, based on Pushkin's play) and folkloric. Folkloric adaptations, especially fantastical ones, were quite popular in la Belle Époque all over Europe, spurred by increasing urbanizing and distance from peasant innocence, but many Russian composers of the day made them their specialty. Rimsky-Korsakov's most famous pieces are in this vein, such as his "orientalist" pieces like Sheherazade, and his acolyte Anatoly Lyadov crafted The Enchanted Lake, one of his most celebrated pieces, in this vein. And wouldn't you know it, both of these guys tipped their hats to ol' Babby Yags.

Lyadov's other most celebrated orchestral miniature is his sinister scherzo Baba Yaga, op. 56, as good a model for 19th century witchy writing you'll see outside of Berlioz. Actually, not so far outside, as many of the tricks employed show up in that witch's sabbath at the end of Symphonie Fantastique, such as a jerkily jaunty compound meter, loud full-orchestra stings and chromatic skittering. There's also a lot of Wagner in the language, such as the dated, yet classic, use of chromatic downward planing ripped right out of the ride of the Valkyries. Dating from 1905, Lyadov's piece is a bit, I dunno, passe (?) for the time, its tricks a little played out and familiar. As much as I appreciate Lyadov's piano music not everything he wrote was indispensable, though this is an easy and welcomed addition to any Halloween concert.

There are similar techniques at play in a considerably older piece yet in some ways more memorable piece, written in 1862 by one of the lost-and-found fathers of Russian classical music, Alexander Dargomyzhsky. Dargomyzhsky is almost totally unknown to mainstream Classical music fans, never achieving much success in his home country or abroad during his lifetime, but his opera The Stone Guest was highly regarded by the Mighty Handful and was considered the gap between the work of Glinka, the earliest Russian composer of international note and one who set the stage for all those who came after, and the Handful themselves. None of his pieces have entered the standard repertoire since his death but I certainly hadn't heard of Baba Yaga, Fantasy-Scherzo before researching for this article, and chances are I'd have gone my whole life without hearing it. The latter half of the piece is definitely witchy enough, starting off on another jabbing bassoon solo, but the mood before it is much more staid, even tragic, and the use of more conventional minor and major chords rather than a smorgasbord of diminished schmears lends the piece an air of dignity unseen in many horror-themed works. Biographical info on Dargomyzhsky in English is scanty, at least over the internet, but part of me would like to think that he took the inherent ambiguity of Baba Yaga's appearances in folklore to heart. It's hard not to be fascinated by a villain with more human qualities than not, and of all the Baba Yaga settings it's the one that seems the most like a portrait of a person rather than a Satanic imp.

Originally I was going to discuss Rimsky-Korsakov's 1880 Fairy Tale, op. 29 here as another Baba Yaga setting, having been brought to it as per IMSLP's subtitle for it on the work's page there. Upon listening to it, though, it seemed a lot less sinister than I was expecting. Then I took a look at the description of the recording I had found and saw that it was based on Pushkin's prologue to his poem "Ruslan and Ludmila", based on a corresponding folktale. "Ruslan and Ludmila" is a wild and fantastic tale of similar vintage and flavor as Baba Yaga, and also features her signature hut on chicken legs, and it was this connective tissue, as well as Pushkin's other allusive indications, that inspired the Fairy Tale, or Skazka. The skazka, translated alternately as "fairy tale", "folk tale" and just "tale", became a quite popular miniature piano form among Russian composers in the decades following this one; Nikolay Medtner wrote so many of them he was practically hip-deep in them by the end of his life. Whereas the piano skazki were short, dramatic works similar in feel to the ballade or legend, Rimsky-Korsakov's use of the title is of course more literal and much more extensive. Clocking in at three times Lyadov's Baba Yaga, the piece eschews curtain raising in favor of creating a diffuse atmosphere of magic and mystery, maintaining the fine sense of thematic architecture shared by Sheherazade and others but removing the need to trundle the audience along on storytelling rails. There's a lot to like here, especially the orchestration; Rimsky-Korsakov was the great creative master of his scene in that regard, and not only are his ideas masterful they are also brilliantly balanced and paced, never blowing out the speakers and perfectly matching the sense of wonder and unease he was trying to create. It's not exactly Halloween, per se, but it is fantasy and went over well with audiences at the time, though I can see why it's not one of his more popular works - 15 minutes is kind of long for what feels more like an interlude rather than a main piece. Still, I'm glad I got to hear it and the relationship it has with Baba Yaga is quite intriguing.

However, there's one piece that you're all waiting for, one that will define Baba Yaga for all time. You know, that one that was written by a Mighty guy and later orchestrated by a master Impressionist and was inspired by a painting of a clock? Yeah, that one.

This one is now and forever the most famous Baba Yaga piece out there. "The Hut on Fowl's Legs" is the 9th movement of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, a piano suite based on paintings by artist and architect Viktor Hartmann created during his travels. The Baba Yaga painting used as a reference for this movement wasn't of Ms. Yaga herself but rather was of a clock modeled after her hut:

That's a pretty boss clock and this is a pretty boss piece. While the other pieces might have depicted the hut standing or stalking, this one has it running at full speed, or Babs Yags flying in her mortar depending on who you ask. Mussorgsky had a knack for depicting energy and savagery in his music and here the language is at once terrifying and cathartic, each percussive slam matched with a surprisingly satisfying harmonic shift or fresh motive. Pictures was highly regarded by the Impressionists among Mussorgsky's other works for its progressive language, and some people argued that Mussorgsky's unique voice was due more to a lack of formal education than creative will. Whether that's true or not is not for me to make the final call on, but what I can make the final call on is its balderdashedness in terms of modern relevance or intrinsic value. I've performed this piece before and as exciting and fulfilling as it is to perform the whole work this one is probably the most entertaining from the musician's point of view, and in a normal article this would be the rousing closer. And it is - if you don't like piano music.

It could be argued that there was no ballet company more singularly important to musical and theatrical history than the Ballet Russes under the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, a company that mounted the revolutionary first productions of Debussy's Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune and Stravinsky's Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. Even though it's impossible to objectively prove it, no other company has been more talked about and lauded, from the mindblowing choreography of Vaslav Nijinsky to the sheer number of bleeding edge composers whose music was mounted. Another seminal name is brought up in more academic circles and isn't nearly as famous as Nijinsky's, the set designer Alexandre Benois, and any time we can talk about Benois is a good time. Educated in Paris, the Russian Benois returned to Moscow and founded the periodical World of Art which did much to promote Aestheticism and art nouveau in Russia. He moved back to Paris in 1905 and spent most of his time as a set designer, principally with the Ballet Russes, and his designs for their productions of Les Sylphides, Giselle and Petrushka are all considered masterpieces in the field, the last one of which has been revived multiple times to great success. He also served as the curator of the Hermitage Museum in the first decade following the October Revolution where he did much to preserve Russian art history. Before all that revolution and ballet stuff, however, he produced one of his most beloved works, The Alphabet in Pictures, a picture book of the Russian alphabet for children. Each letter is assigned with a colorful subject, many having a specifically Russian cultural reference, and the results are simply stunning. Original copies of it fetch up to $10,000 in auctions and I can't say that I disagree. In 1910, Nikolay Tcherepnin, the first in one of the most successful compositional dynasties in Russian music, composed a piano suite based on 14 of the 36 represented letters (the alphabet was reduced to 33 in 1918), and a recent recording by David Witten brought it to my light as well as the world's - and wouldn't you guess who flew in with a mortar and pestle.

It could be argued that there was no ballet company more singularly important to musical and theatrical history than the Ballet Russes under the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, a company that mounted the revolutionary first productions of Debussy's Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune and Stravinsky's Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. Even though it's impossible to objectively prove it, no other company has been more talked about and lauded, from the mindblowing choreography of Vaslav Nijinsky to the sheer number of bleeding edge composers whose music was mounted. Another seminal name is brought up in more academic circles and isn't nearly as famous as Nijinsky's, the set designer Alexandre Benois, and any time we can talk about Benois is a good time. Educated in Paris, the Russian Benois returned to Moscow and founded the periodical World of Art which did much to promote Aestheticism and art nouveau in Russia. He moved back to Paris in 1905 and spent most of his time as a set designer, principally with the Ballet Russes, and his designs for their productions of Les Sylphides, Giselle and Petrushka are all considered masterpieces in the field, the last one of which has been revived multiple times to great success. He also served as the curator of the Hermitage Museum in the first decade following the October Revolution where he did much to preserve Russian art history. Before all that revolution and ballet stuff, however, he produced one of his most beloved works, The Alphabet in Pictures, a picture book of the Russian alphabet for children. Each letter is assigned with a colorful subject, many having a specifically Russian cultural reference, and the results are simply stunning. Original copies of it fetch up to $10,000 in auctions and I can't say that I disagree. In 1910, Nikolay Tcherepnin, the first in one of the most successful compositional dynasties in Russian music, composed a piano suite based on 14 of the 36 represented letters (the alphabet was reduced to 33 in 1918), and a recent recording by David Witten brought it to my light as well as the world's - and wouldn't you guess who flew in with a mortar and pestle.

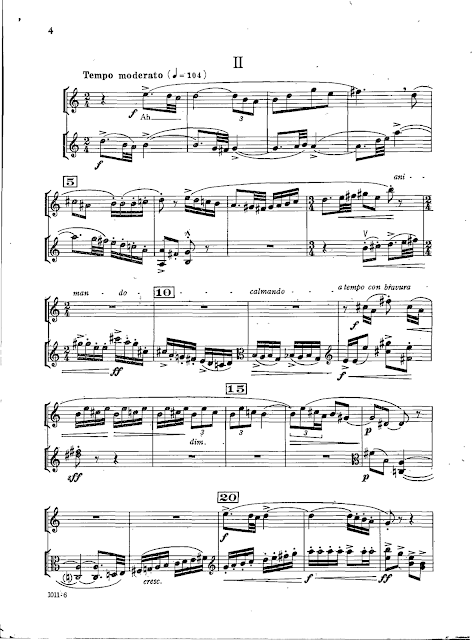

It's debatable whether or not this is more experimental than Mussorgsky's Baba Yaga (though the fact that Mussorgsky's piece was written decades earlier most likely answers that question immediately) but it can be said that Tcherepnin's Baba Yaga is easily the funniest. The tinkling arpeggios plopping on augmented chords is more akin to the improvisatory caprice of Debussy's "Le poisson d'or" from his second book of Images, and the cute ppp ending chord is equally spritely. However, most of the piece is a black gallop, that offset bass pattern bumpity-bumping chromatically contracting and expanding chords in the right hand. The tunes might not be as iconic as Mussorgsky's but Tcherepnin more than makes up for that with his expert piano writing, as detailed and subtle as anything of his day, and believe me that there was a heck of a lot of competition. And why can't there be room for a funny-scary Baba Yaga? The set came from a kid's picture book and the tone is properly accessible throughout the suite, so a witch that's a bit humorous is exactly the kind of thing kids love at Halloween. It'd make a fine encore as well, totaling a mere 1'20'' for a witchy bolt off stage*. It can't really be the encore for this article, though, as I've spent the most amount of time talking about it of all the pieces and even included the sheet music for the benefit of busy work scrolling - perhaps I'm trying to tell you that there's a certain Russian composer that we'll be talking about next week, one whose name rhymes with "pickle-eye"...**

~PNK

*Somebody needs to get on a Baba Yaga hut costume right pronto.

**Hey, more costume ideas!