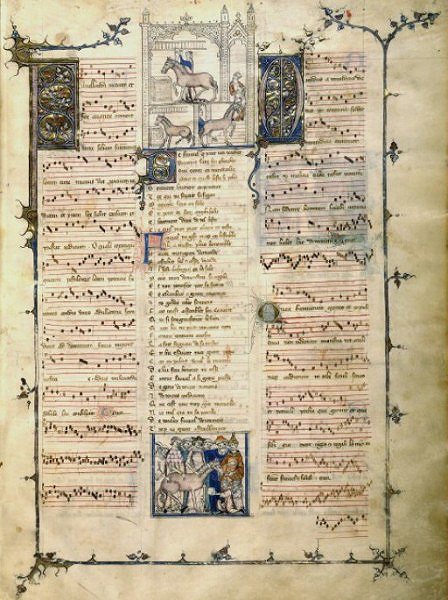

Books are no longer worlds. I don't mean worlds like the book from The Neverending Story, though I'd put dollars to donuts people would snap up those volumes before they could blink. I mean artistic worlds, all-encompassing artistic objects - the kind of vast, hand-crafted tome from pre-Gutenberg Medieval Europe, the kind that inspires wonder and hunger in antique book collectors and fantasy consumers. Because there was no way to exactly reproduce anything before the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century, the requirement to remake everything by hand inspired a great deal of individuality, either intentional or unintentional, in format, illustration, and scope. Many music history students come across Roman de Fauvel in their required reading, a 14th-century French allegory about a horse who rises to power in the French court and embarks on various satirical misadventures. One of the earliest copies of the book comes with 169 musical insertions that span the breadth of Medieval music and allow for entrancing design opportunities such as this page:

This era also produced a trend for what is now called "eye music", notation in the form of a visually recognizable object or symbol, such as this gem:

The shape has no effect on the sound of the music, but rather is a holistic touch in a medium that over time would become more and more narrow in its look and feel. It naturally went away with standardized printing, as does anything expansive and innovative in life, and the concept of engraving outside the box didn't come back until the 60's had something to say about it. You remember our old friend Burr van Nostrand, don't you? He was aided by the counterculture and his work is a fully-formed, organic anarchy, like Shel Silverstein was possessed by John Cage. However, the most famous 20th century composer to work non-musical sight elements into his work is without question George Crumb, whose Makrokosmos sets for piano have adorned hundreds of college dorm walls since their inception in the 1970's:

While these guys were breaking American Mold there was another guy on the other side of the pond who wouldn't leap as intensely into the eye music fold but would return a Medieval past all the same (no, not Arvo Pärt). Hans Otte (1926-2007) isn't a name that would leap out of the bushes of your local record store to bite your aural jugular, and he wasn't that name in Europe, either. A longtime music director for Radio Bremen, Otte was unique in his steadfast promotion of the 60's Avant-Garde in America, specifically the John Cage/David Tudor/Terry Riley/La Monte Young continuum. Minimalism never really caught on among European classical composers (who were so deep in the dodecaphonic cookie jar they wouldn't have anything to do with vast swaths). There was a big minimalist movement in progressive rock (specifically Krautrock) and midbrow electronic music, with figures such as Jean Michel Jarre, Holger Czukay, and Klaus Schulze coming to the fore on parallel tracks to Brian Eno. It's this lack of academic engagement in minimalism that lets Otte stand out, and his method was both delicate and enveloping, modern and ancient, down-to-Earth an spiritual all in one.

His most well-known work is The Book of Sounds (1979-1982), and even if he died the second after he inked the last note it would still loom high in late-20th century piano rep. He played it quite frequently during his lifetime and a cursory glance through the interbuts reveals a plethora of performing admirers. Properly notating minimalist pieces can prove tricky, as literally writing out each repetition induces madness in both the engraver and the consumer, and sticking repeat signs on every other bar is a clunky solution. Otte's novel approach puts elegance and open space first, a system I've only seen matched in appeal by György Kurtág's unique system:

The performance included above is only one such solution, and no two performances are alike. These pieces hinge simultaneously on precision and instinct, and The Book of Sounds facilitates both of these forces without getting in the way of a good-looking score. Less is certainly more, and the lack of some recognizable elements in the staff allows for others to be expanded and exploited. Sometimes a visual collision occurs, such as this charming latticework:

It's important to know where all of this came from, and along with the official explanations of Eastern spirituality and championing of American minimalism, certain earlier works point to another source:

Being quite the far cry from my thesis, this work is a fine example of the 60's new music atmosphere surrounding the iron curtain. The major players in this kind of monumental, gesture-based music were Witold Lutosławski and Krzysztof Penderecki. While Penderecki's works eventually diverged from 12-tone blocks,

Lutosławski stayed firm and fashioned serialism into a vehicle for pure musical drama, allowing systems and jargon to melt away and seducing audiences with passion and movement. Like

Lutosławski's best, Passages is a bestiary of timbre, occasionally edging into farce but largely staying within the realms of concert-hall terror. The most notable moment is at 5:45, where the orchestra gives way to reveal a D-flat major chord spread across the strings, a chord that wouldn't have been half as powerful without everything that came before it. Sometimes beauty comes from withholding what we most anticipate, and Otte is nothing if not a master of pacing.

The Book of Hours (1991-1998), while not nearly as popular as The Book of Sounds, is just as worthy, spreading 48 pieces across four volumes in page-long increments. Otte continues developing his notational scheme but, rather than slipping into modal complacency, lets chromatic linelets ping into the distance. Pedal saturation is a given, and forward momentum is nil. The only YouTube performance I was able to find was of the entire set, and I'm assuming you don't have an extra hour to spare, so don't feel obliged to watch the whole thing. The act of reproducing the composer's manuscript brings the reader back to the handmade nature of illuminated manuscripts, where each copy is unique and the scribe can be felt through the book. One element that rears its lovely head more than in Sounds is physical space between notes, and part of his notation allows notes to be held longer if there is more blank space after it than others. This is a tricky game to play, and it wouldn't work at all under a different musical reading history than ours. Thankfully, most people seem to get the drift:

There's plenty more to see, of course, and the lack of clandestine uploads of his scores may be more of a boon than a problem. As with Medieval manuscripts, their singularity and physical beauty intimates a mystical quality that ordinary printed music lacks. As with any object worth finding, the search is a major element, even if that search is nothing more than a simple online order form. If I were you, I'd abscond with the nearest copy of your favorite Otte Book and head for Mont St. Michel, perhaps camping out next to its ancient clock with an oil lamp and a wheel of brie. In a few hundred years Otte's work will perhaps be confused with sacred tomes or New Age manifestos, and perhaps that's for the better, and perhaps we can all group the Books with Charles Koechlin's Les Heures Persanes and Kaikhosru Sorabji's massive cycles as the closest the piano has gotten to a religious experience.

~PNK