If there's one thing that's rare in the classical music world, it's disgraced figures. There have only been a handful of controversial cases of classical artists being called into question and thrown out of their respective circles, such as Solomon Volkov's Testament: the Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich and its dubious authenticity, or the ejection of Léon Delafosse from Marcel Proust's artistic circle (a story for a later time). One crime that I've heard almost none of is plagiarism, specifically compositional plagiarism, and it may be for a disgust with the perpetrators that there is a lack of cases in the accessible literature. Of the scant handful of plagiarist composers I've heard of, one begs further investigation, as his story is as fascinating as it is mysterious - Dante Fiorillo (1905-?). His alleged musical theft may have ensured his extreme obscurity, but it also helps when you disappear for no apparent reason.

A native of New York, Fiorillo was apparently self-taught as a composer, but studied cello at Greenwich House Music School. By his own admission he wasn't much of a cellist, but that didn't stop him from finding his way to Yaddo, one of the Northeast's most needs-no-introduction-ish art colonies. He also had no trouble gaining the love and support of Yaddo's guests, partially by his character but helped in no small part by his perpetually poor health. In addition to winning the Society of Professional Musicians award, several guests rallied for him and helped him secure the first and second of four consecutive Guggenheim fellowships (1935-1938), and he was appointed as Composer-in-Residence at Black Mountain College, a short-lived but seminal experimental institution dedicated to an overarching presence of the arts in a liberal arts education. The President of the Guggenheim foundation, Henry Allan Moe, thought that Black Mountain College would be a comfortable, supportive environment for Dante and his delicate composure, and kept a close watch on his productivity and health. The eccentric and ailing composer required two quarts of milk a day in addition to what he had with meals, and Moe made sure that he was given a warm thermos of it each night before bed. Fiorillo was a charming presence, an excellent storyteller and magician, and the poet Theodore Dreier noted in letters that he was "in danger of being sued for alienation of affection by all the dog owners, -they have all deserted their masters for Dante."

Moe also supplied him with composition paper whenever he needed it, and he turned out to be quite productive, authoring at least four orchestral (?) suites and possibly a fifth as well as many other works, including the Concertino for Piano and Strings, which was performed by the Promenade Symphony Orchestra to three curtain calls. His compositional style was appreciated, with fellow Black Mountain composer Allan Sly (who was the soloist for the Concertino premiere) describing his style as "(seeming) to flow from a deep well of Italian fecundity, with facility." However, Sly noticed one day that one of Fiorillo's new works bore a striking resemblance to a composition sent to him by a German composer. At that time a conductor, Fiorillo came into contact with a pair of German composers, Berthold Goldschmidt and Karl Amadeus Hartmann, who at that time were unknown in the U.S. and were struggling to get their work recognized. New music was still a nascent market in the U.S., a near-vacuum that would be quickly filled in the decades following WWII. Fiorillo claimed that if they sent him scores he would perform them stateside, and they enthusiastically obliged. Goldschmidt recounted later that he was confused by the lack of follow-up correspondence from his American friend, and some time later was sent reviews of the premieres with the composer's name carefully removed. Once he got his scores back he realized they hadn't been used in performance, and showed signs of being used for copying. I don't know how many more composers Fiorillo did this trick with, but it didn't take long for Sly, Moe and other composers to uncover the truth. Fiorillo was forced out of Black Mountain College in 1938, but that apparently didn't stop him from winning the Pulitzer Prize that year (a scholarship, as the Pulitzer Prize in Music didn't exist until 1943), or receiving continued support from Moe.

The Pulitzer award was won largely based upon his eighth symphony (of twelve!), and in researching him I found a fascinating and somewhat ridiculous newspaper article on the win from the May 26, 1939 issue of The Milwaukee Journal. That picture at the top is the sensational headline, coupled by a sensational, Depression-hugging thesis of the symphony's genesis being the plight of a poor immigrant boy suffering in New York slums. I have to assume all the information in the article came from the proverbial horse's mouth, so I can't be sure of what is real and what is not, so don't say I didn't warn you. Fiorillo was the child of Italian immigrants, growing up in the slums to the companionship of dirt, noise, and darkness. As the article says:

There are places in the slums where the sunbeams cannot enter because the houses are too close together. But no place is too dark or too remote to be reached by the sound of music.

At first that sound had to be made by Fiorillo himself. He was always looking for escape, and as a small boy made considerable trips in order to walk the "nice streets". His father bought him a harmonium when he was seven, and he started learning music by ear, entering the Greenwich House Music School at age 14. Miserable in his cello studies, he studied the works of the old masters and used the cover of practice time to write works of his own. After some months he came into contact with Enrique "Hank" Caroselli, an Uruguayan immigrant and head of the school, and he was befriended by him along with many of his friends. In addition to teaching them performance technique he insisted upon proper character and appearance, and his love and support was the inspiration for Fiorillo to go on in music. The article stated that Caroselli wanted no praise, saying that his work was its own reward and that he was passing on the teachings of his own mentor, the Belgian violinist and composer César Thomson. The article concludes with a similarly boil-in-the-bag inspirational close, seeing Fiorillo's example as a charge for the 335 lower-class students at Greenwich House:

They stand around in groups reading the newspaper clippings of the Pulitzer award on the school bulletin board. The saw away at their fiddles and hammer the piano keys.

For Dante escaped from the slums through music. May not they?

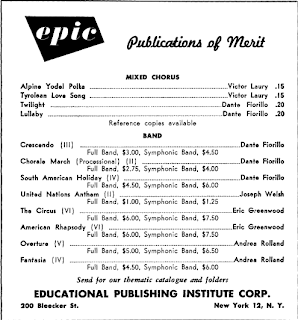

Despite his dubiously continuing success, Fiorillo's story comes to a close soon after. In the late 40's he started a music publishing company, the Educational Publishing Institute Corp. (EPIC), which published a number of his own works as well as those of other now acutely obscure composers. Considering that new music publishing, including works by foreign composers, and musical communication in general was better facilitated in post-WWII decades, the notion of Fiorillo continuing to plagiarize seems dubious, and plagiarizing pedagogical music is an extremely sad notion indeed. An ad for some of their publications doesn't bode well, despite their "merit":

He appears to have taught at the Eastman School of Music (possibly as late as 1953) alongside Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers, and that's pretty much the last information I was able to find on him. He disappeared from the New York music scene in the 50's, 1950 exactly according to one source, and a suspicious-looking death date of 1955 from another source may be another eligible disappearance date, which would clear up room for the 1970 death date I found on his German Wikipedia article. The presence of a German article but not an American one is fascinating to me, considering that this never happens with American composers. Was it written out of spite for his copying of the works of such luminaries as Goldschmidt and Hartmann, or is it actually easier to find information on him in Germany than it is here? The latter is ridiculous, but with the puzzling cloud surrounding Fiorillo and his work I'm open to any possibilities. Considering that the article didn't link to a source for that death date and there are no details to go along with it, Fiorillo may as well have become a hermit in the Adirondacks or passed into another dimension for all the clues I've been given.

Want to know what his music sounds like? I would too, because there isn't a single commercial recording of his work and only two archival performances, one the Yaddo Chamber Orchestra in the New York Public Library and the other by the Amerita String Orchestra at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the Library of Congress. The latter dates from 1959, and it may be the last time anybody thought about his work. As I'm no longer a university student my Interlibrary Loan abilities have been cut off at the knees, so it may be quite a while before I see any of his scores. Considering that he was self-taught as a composer, and he gained his recognition in an era of American music that was open for pretty much anything, it's possible that the works he wrote himself didn't sound like anything else at the time. The real kicker is that I found him purely by accident. I was searching Worldcat for pieces for voice, violin and cello, and I stumbled across the four manuscripts of his in the New York Public Library donated by George Rochberg. I don't know how Rochberg got a hold of them, but they are dated to 1942, and Rochberg was freshly out of college at that point, so it's not entirely implausible that he met Fiorillo around this time, even though he never attended either Eastman or Black Mountain and served in the Army during WWII.

One person who knew him and is still alive is the composer Walter S. Hartley, a man most famous for writing sonatas for every instrument of the orchestra as well as all the saxophones. I found that he was a student of Fiorillo's while at Eastman, and I sent him an e-mail through his personal website. Considering that Hartley is 85, I was worried that he didn't check his site's e-mail address frequently or at all, and that he may have forgotten Fiorillo entirely. Fortunately he got back to me the next day:

Dante Fiorillo gave me private lessons in composition at his apartment on Bleecker Street, NY several times in Summer 1949 and 1950. As I remember they involved counterpoint, and were very helpful in my development. He was born in 1905 and died in 1995 (this is all I could find about his life). He was very intense and had strong opinions about fellow composers the nature of which I can't remember.

Dante Fiorillo gave me private lessons in composition at his apartment on Bleecker Street, NY several times in Summer 1949 and 1950. As I remember they involved counterpoint, and were very helpful in my development. He was born in 1905 and died in 1995 (this is all I could find about his life). He was very intense and had strong opinions about fellow composers the nature of which I can't remember.

This lines up with a disappearance in the early 50's and trumps the other two death dates by a good 40 and 25 years respectively. I don't know where Hartley got that 1995 date, but it's certainly a plot thickener. It's always interesting when an artist is painted as being opinionated; that term more often than not causes images of cranky old men and disrespectful youth to arise, but is wide enough to include just about anything. I wonder if anybody valued opinions that strong after he was found out, but it appears they didn't get a chance to after his disappearance.

Is the crime of plagiarism so vile that Fiorillo is worth forgetting? Ultimately I can't say. I founded these blogs on the belief that all art has some value, and there are many fine artists with unfortunate personal lives and regrettable personalities whose work is more important than their biographies. The problem with putting Fiorillo in that pile is the uncertainty in what work is actually his. It's not like he didn't have his difficulties in life, and his continually poor health is an important detail. Was he under a lot of pressure and just couldn't make the effort to keep up with his previous pace? Perhaps he requested those German scores under an initially pure intent, only later seeing the window and jumping through it.

Is the crime of plagiarism so vile that Fiorillo is worth forgetting? Ultimately I can't say. I founded these blogs on the belief that all art has some value, and there are many fine artists with unfortunate personal lives and regrettable personalities whose work is more important than their biographies. The problem with putting Fiorillo in that pile is the uncertainty in what work is actually his. It's not like he didn't have his difficulties in life, and his continually poor health is an important detail. Was he under a lot of pressure and just couldn't make the effort to keep up with his previous pace? Perhaps he requested those German scores under an initially pure intent, only later seeing the window and jumping through it.

I once read a biography of Ruggiero Leoncavallo, the one-hit-wonder composer of I Pagliacci, and it turned out to be a fascinating story of a mediocre artist whose ambition far outreached his talent and discipline and would string along publishers with false promises, taking long vacations based upon claimed ailments. It's important to remember that creative figures, no matter how brilliant, are nothing more than human, and finding stories like Leoncavallo's are an affirmation of how tenuous the line between artist and layman truly is. Was Fiorillo a good composer? I may never know, and nobody is eager to find out for me. He was certainly never short of friends, and his history of adoration and awards suggests a good fortune that eclipses his actions. His behavior didn't stop his scores from entering university circulation, and if Rochberg had the capacity of charity to save a handful of his scores (four of only 20 that I know survived whatever wraths time threw at his large oeuvre), it's a testament to his art and life that warrants investigation more extensive than my own. The only way historians can progress in their craft is to leave morality out of their work, ensuring a purity of truth, or as best a truth as they can muster. If stories such as Fiorillo's fall through the cracks of music's past we'll be at a loss of learning experiences and at the very least some fascinating little episodes. I don't think that this article is unwarranted in its charity, and it certainly wasn't a trial to write. If anybody out there has more information than I was able to find I'd be more than happy to hear it, and if I wish for anything it's for more stories of music's singular figures to surface, the illustrious and the unpalatable.

~PNK

~PNK

Sources: The Arts at Black Mountain College by Mary Emma Harris; Black Mountain College: an Experiment in Art by Vincent Katz, Martin Brody, Robert Creeley and Kevin Power; Yaddo: Making American Culture by Micki McGee; Harpsichord and Clavichord Music of the 20th Century by Frances Bedford; "Escaped Slums with Music that Won Pulitzer Prize" by John Lear - The Milwaukee Journal, May 26, 1939; "Berthold Goldschmidt: Orchestral Music" by Colin Matthews - Tempo, New Series, No. 148 (Mar., 1984); John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation page (http://www.gf.org/fellows/4585-dante-fiorillo); personal correspondence with Walter S. Hartley

Dear Mr. Nelson-King,

ReplyDeleteLooking through photos on eBay, I found one of Dante Fiorillo, along with a newspaper clipping about his Pulitzer. I'd never heard of him, and was curious about his bio, which led me to your fascinating article. You can find the eBay listing here:

http://www.ebay.com/itm/Vintage-photo-RPPC-Autographed-Pulitzer-Prize-winner-Composer-Dante-Fiorillo-/231157418871?pt=Art_Photo_Images&hash=item35d20e4b77

Sincerely,

- Ryder Windham

Thanks for the link and the kind words! I bid on it, and soon may be the only musicologist with a photograph of Dante Fiorillo. His story only grows more fascinating with each clue. Thanks for the support!

Delete~PNK

I am an 82 year old woman and was a grateful student of Dante Fiorillo when he taught at the Randall School for Creative Arts in Hartford. Since I was ages 8-13 at the Randall School, where he and his wonderful wife Rafaella Tomasonni (who taught drama) taught on weekends, and also stayed at my parents house, I figure this must have been around 1950-1956. Dante was a wonderful teacher of us children, mainly on percussion instruments, but also he taught us how to compose music! Even set up the little grids and fill in the notes ourselves. When we played badly (as we often did), he would sometimes yell, humorously, "Spaghetti on toast, spaghetti on toast." (the worst thing he could imagine. He was also very much into ESP and psychic experiences and explained to me, a fascinated child, how his brother Michaelangelo, also was psychic. I,as he reminded me, absolutely was not. He also taught me an important life lesson when I and my friend Toni Randall (daughter of the Randall School founder Ann Randall) once snickered at some poor, shabbily dressed children who showed up in out class. "I am so disappointed in you girls," he said. "These children are poor. They can't help how they dress." I felt like falling through the floor in shame. It may even be that this significant moment, played a role in my later activism for labor unions and women on welfare. I don't know, as there were other influences, but...Anyway, Dante and Tommi (as we called his wife, a marvelously creative, kind person) were bright spots in my childhood and whatever he did or didn't plagiarize, I will always be grateful. He certainly was alive and kicking in the 1950's, so the 80's report of his death is probably accurate.

DeleteVery fascinating article. About 45 years ago I came across Signore Fiorillo (not literally, just references to him) and chased down everything I could find, including scores in the Fleisher Library in Philadelphia. I read through them quickly and didn't conclude anything about their genuineness. I wrote to everyone I knew of who knew Fiorillo and didn't get a single reply.

ReplyDeleteWalter Hartley was a teacher of mine 52 years ago. In 2005, he told me more or less what he told you plus a little more. I had given up looking for information about Fiorillo long before the Internet came along.

You may be interested in my site, www.quartetweb.org. There are a few stories there, although behind the scenes, mostly.

He probably died on October 21, 1995 in Brattleboro VT. He had lived in the Bronx. Alas, I probably could have found him.

DeleteThere may be a son born in 1938.

Thanks for the info and kind words. I recently won an autographed photo of Fiorillo along with a newspaper clipping on eBay (see the first comment above), so I'll be adding that to the blog. I'd go to the Fleisher Library myself if I lived on the East Coast.

DeleteHello Peter,

ReplyDeleteMy name is Michael Fiorillo, and I am the nephew of Dante Fiorillo.

I'd like to thank you for your ample research, most of which I was unaware of.

As your post amply suggests, my uncle was quite a piece of work, and I many amazing/amusing/shocking, if mostly uncorroborated, stories about him. The plagiarism charges were known, but you delved in to greater detail than I was aware of.

If you'd be interested in further correspondence/discussion about Dante, email me at ginseng4@earthlink.net.

Did you know Dana, Dantes son?

DeleteReply to pete@peteandcompany.com

in the SSDI (Social Security Death Index) Dante Fiorillo is listed as having died in October 1995. I looked for him for years, corresponding with several people who claimed to have seen him as late as 1986 in New York City. I would like to know if Paul Rapoport has an obituary for Vermont.

ReplyDeleteMr Nelson-King,

ReplyDeleteI am Dante Fiorillo's granddaughter. He was as enigmatic in his family as his art. He did die in 1995 in Vermont. I would be willing to share some of what I know of him and understand that there is a professor in Florida researching him as well,

I can be reached at fiorillo42@gmail.com

hey mom

DeleteI was a friend of Dante Fiorillo from about 1975 until his death in 1995. The following statements are also approved by Ina Beck, a companion from 1968 to 1995. I am writing from Ina's kitchen. Ina also maintained a friendship with some of Dante's circle, from whom Ina learned most of what she knows about Dante's early life.

ReplyDeleteI like Mr. Nelson-King's thoughtful and expressive attitude and writing style. Ina also thanks him for explaining some things she did not know. We also all seem to agree that much about Dante Fiorillo is both unclear and may never be proven. Nonetheless, someday someone might want to do research which probably could prove or disprove some of the most serious allegations. Also, there are a few instances where Mr. Nelson-King seems to have made unwarranted assumptions.

I do not have time to say everything I would like. So I will just try to list the main topics. If anyone has or wants more details or discussion, reply here or seek out my Facebook page.

• Ina has many photos and music manuscripts of Dante Fiorillo. She is very knowledgeable and believes that Dante's music includes possibly great works which should be published before they are counted among the lost. Anyone with a serious interest is welcome to examine these documents.

• They became impoverished during the depression, but Dante's family was not initially poor. His father was a professor at the University of Bologna. And--contrary to Mr. Nelso-King's assumption--it is quite a stretch to assume that any quaint news article was approved by Dante. Dante told me that his father bought an old farm as a vacation home. Dante said that a reporter therefore said that he grew up on a farm and got his ideas while pushing a plow. Dante's father was furious and wanted to initiate a lawsuit. Dante said that he did not want the fuss but later regretted not making a fuss.

• In the 1970's, Dante was listed in encyclopedias as "a prolific Italian-American composer." Then about 10 years ago, a search revealed him offhandedly referred to as "a plagiarist." It is difficult to understand how a known and prolific composer's works could all be presumed plagiarized and worthless. Especially after receiving both a Pulitzer and four Guggenheims.

(Continued next message.)

• When I first heard of the plagiarism allegations, I assumed they began after the awards. It is surprising to find that the supposed incident was well before the awards. When exactly did these allegations begin and from whom? Dante had many left-leaning political views which were seriously "unAmerican" for the times. He was referred to as "The American Mozart" and had several traits in common. Early development. The ability to memorize and compose complex works in his head. The lack of ability to handle money or navigate politics.

ReplyDelete• The way I hear some allegations, they might at worst be explained as subconscious accidents due to Dante's method of composing in his head. That described here seems quite different. Nonetheless have you ruled out the possibility that Dantte was the victim of some kind of scam or misunderstandiing? According to Ina, Dante was involved in trading manuscripts.

• Dante is said to have earned money during the depression by giving classical orchestrations to popular works. He often used this money to help others who were even less fortunate. He also worked as a music teacher for poor children in the depressioni era WPA program. This was confirmed by a fellow participant who posted an internet message about ten years ago, "Whatever happend to Dante Fiorillo?"

I may post other questions and points later if anyone expresses interest. Thank you for an inspiring and interesting article.

My grandfather's family did indeed own land and build a house in Prattsville NY. It stayed in the family until my great uncle Joaquin's death 19 years ago. The article about growing up in the slums was overblown at the very least. I have some of his scores. If you'd like to reach out about his later years with Ina, I would love to hear more.

DeleteI have a copy of a letter from his wife (Mary) notifying a fan that Dante's *quintet in F Minor* will be performed on

ReplyDeleteJuly 2, 1938 at noon on NBC New York station WFAI or WEAI, (I can't quite decipher the 2nd letter in the radio station's call sign). The note is written on Guggenheim Foundation stationary.

That was my grandmother Mary Kelly Fiorillo, nice to see her named.

DeleteI knew Dante for may years as I lived in the same appartment building in Riverdale, New York. Is Ina still alive? What has she done with the manuscripts? I think his daughter Christina who lives in Scotland should have some of his sheet music

DeleteI wrote 2 comments above in April 2018 -- somehow ascribed to "unknown" instead of Krystof Huang. Anyone wishing to contact me can easily do so on Facebook. To be sure to be noticed -- I suggest both a Facebook "message" and "comment" on any of my Facebook posts.

ReplyDeleteRecently i clarified several life-long questions by using the new a.i. searches. today, september 25, 2025, it suddenly occurred to me to do this for Dante Fiorillo.

I was disappointed to find only this 2013 article.

However -- i was pleased to find several updates and new messages. Especially by Andrea Fiorillo. I will try to discuss with her before i say anything more. i have several new thoughts both pro and con the reputation of Dante Fiorillo.

just let me say Dante is not the only puzzle. how books and articles can suddenly list him as a "known plagiarist" -- without clarifying the depth or degree -- is rather inexcusable.

on the one hand -- i tend to assume the worst. mostly because respected experts seem to say that without being challenged.

on the other hand -- "Song Sung Blue" by Neil Diamond is a plagiarism of Mozart's Piano Concerto #21. Practically everything from Shakespeare to Elvis was a plagiarism in some sense.

I tend to assume that "a known author" who dismisses Dante Fiorillo in one phrase as "a known plagiarist" probably knows what he is talking about.

On the other hand -- by the same token -- and given the wide range that might be considered "plagiarism" -- why do the experts not clarify the details?

i want those details before repeating the accusation. So should anyone, in my small opinion. maybe this has been clarified in updates to the article above. I will read it again. in addition to attempting to contact Andrea Fiorillo. if i do not comment again it is probably because if failed to contact her. And meanwhile. thank you anyone who wishes to contact me on Facebook. i will also be notified of any new addition to these comments.