There is an inherent loneliness in seeking unknown art, and likewise in the work of collecting and preserving it. Much of my time doing it is spent pulling scores from library shelves, scanning through eBay listings for random jewels, and lengthy online searches, activities that aren’t known for group interaction. And because the art you end of trying to preserve is unfamiliar for one or some of many reasons, there is a natural resistance in any potential audience, and you risk continued loneliness in your efforts. As such, I’ll occasionally come across a Society, Foundation, website or other effort to be the authoritative one-stop shop for a composer, and in some cases the entire enterprise is run by one person. Sometimes they’re a relation of the composer, but other times they have thinner connections or none whatsoever, such as with Graham and David Parlett’s cataloguing of Arnold Bax’s work. So every now and then I’ll write about a forgotten composer by way of their preserver, and interview the living champion in order to understand what they do, how they do it, and what all this is for.

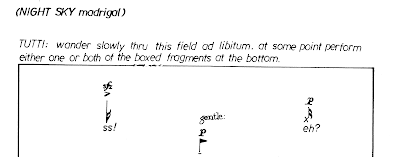

One day some years ago I posted on Facebook, asking my music friends to recommend composers to me that I may not have heard of before. David Victor Feldman, who I had met through modern music groups, sent me scans of two scores by the Yale-educated composer Humphrey Marshall Evans III (1948-1982) who I most definitely had not heard of. The scores, Night Sky Music 3 (1969) and down wanky pleasure lane... (1970), were highly intriguing, dating from the peak of the 1960s-‘70s American Avant-Garde and full of juicy mysteries. Inscribed by hand, they are beautiful graphic works, making players engage with ambiguous spatial notation, complex instructions, theatrical extramusical elements and much more, all imaginative and expertly drafted. But I couldn’t hear any of it, as none of Evans’s works had been commercially recorded and I was unable to play through the pieces myself.

Some time later Feldman created The Humphrey Marshall Evans III Society on Facebook, and he periodically posts scores and fragments, links to Evans ephemera, and calls for recollections and more information from those who knew Evans and his cohorts. Feldman is slowly but steadily building a definitive Evans archive, and the group members, including myself, are quite enthusiastic about his efforts. He seemed like the ideal first candidate for my interview series, so I reached out to him to talk about Evans and the quest to save his work from the dustbin of history. Here’s an opening statement from him:

I heard about Humphrey from Robert Morris when I was an undergraduate. By way of background, Bob was born in '43 and Humphrey in '48, so Bob was just a few years older when he taught Humphrey and Lucky Mosko advanced 12-tone theory during their post-graduate year where they picked up Master degrees in music theory. I was born in '57, so Humphrey and Lucky had left the Yale campus four years before I arrived. Bob had a score to show me, to a piece basically of Lucky's called Outer's Covering: tamara settings for molly, but Humphrey was the guest composer of one of the "settings" (also called "pieces" below). These settings all had titles like "MARILYN and the SHOES", "MARY and the SHOES," "ROBIN and the SHOES," etc. To give you some idea, let me transcribe the instructions:

"GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS 1) Everything is a notation. 2) Each notation (and each fragment enclosed within dotted lines) should be considered contextually, distinct from every other notation. (Similarities in notated gestures need not be perceptible either to performer or listener.) 3) This piece occurs somewhere during a larger nonexistent gesture: it represents neither the beginning nor the end. Since each gesture (and the piece) is conceived as only an inner portion of a larger gesture, always keep in mind the nonexistent beginnings and end of the piece and of each fragment. INSTRUCTIONS for PERFORMANCE 1) The individual pieces may be placed in any order. 2) Any or all of the pieces may be excluded from any or all of the performances. 3) Any number of people, with or without instruments, may perform the settings. 4) Settings may be performed simultaneously and/or consecutively with or without pauses. ALTERNATIVE INSTRUCTIONS And or all of the previous and following instructions may be ignored (including duration indications)."

The settings themselves are striking works of graphic art, with some music notation. You might compare the work to Earle Brown or Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, but they clearly supply graphic improvisation prompts, and this piece drops the performers into ironic and paradoxical quandaries. The composers do seem to having something in mind, but also mean to withhold their explicit intentions. It seems humorous and also trippy. Besides the score, Bob had wondrous things to say about Humphrey and Lucky. Humphrey in particular had won the BMI prize for student composers multiple of times. But there was nothing for me to hear. So I filed the name in the back of my head. For years. Around 1995 AltaVista (the pre-Google) came online and lead me to a webpage devoted to artists dead from AIDS. There was a listing for Humphrey and titles of some works. Still nothing to hear or see. Lucky Mosko got his degree and had a career teaching composition at Cal Arts and conducting new music around the country (with some sort of regular gig at Harvard). Eventually I got to hear some of his music when a CD came out. Years go by again, I have a random-google-moment, and this time Lucky has died and his papers have been settled at Harvard. Among the boxes of Lucky's stuff, there is a box or two of scores by Humphrey and there are tapes, though not many digitized (and what is digitized only available to hear on campus). But I don't live far, so I made some trips to the rare book room of their music library and photographed all of Humphrey's scores, and listened to what little I could. Then I started tracking down Humphrey's friends and by now I have a pretty good picture of his very unusual life, from his home-schooled childhood in India, where his parents were likely spying for the CIA, to his high school years in the DC area, where he became a favorite student of Grace Cushman who ran Peabody's pre-college division, to his years at Yale, his one year at Cal Arts, and then his time in NYC up until his death. He had day gigs, most notably working for the famous publisher Maurice Girodius (who first published Lolita but generally made his money on porn). Humphrey's great success in the publishing industry was discovering V.C. Andrews and making her first manuscript, Flowers in the Attic, into one of the best selling books of all time. But in NYC he stops composing, but unhappily, and presumably becomes an alcoholic as a result. He was a gay man, with a taste for "rough trade." Whether he actually died of AIDS or cirrhosis I'll probably never know. He came down with hiccups that just wouldn't go way, and a month latter he was dead, at 34. That's young to die from cirrhosis, but I have reports that he drank enough to make it plausible. The scores are quite diverse, fastidiously notated, but also generally somewhat open (non-deterministic). His big idea, it seems to me, was to compose for people (with instruments) rather than for instruments (played by people). So he orchestrated with a palate of personalities, rather than a palate of timbres. That said, he meant these pieces to be robust rather than specific to particular performers, so the scores draw out the human being in the performer, whatever the personality might be. But that makes it sound like he composed "`theater pieces," and actually, the notes always matter, he just opposes the alienation between person and personae that typifies classical music practice. And that opposition takes the form of throwing up paradoxes, so that the performer can't simply "serve the composer's intentions," as so many performers see their jobs, but still without everything falling apart into a free-for-all. Humphrey, Lucky and Burr van Nostrand were the "Yale Bad Boys," and they livened up the campus and staged many events that were hugely popular (during the late 60s). Humphrey and Lucky studied with Donald Martino. Martino found them puzzling but basically supported their experiments on the condition that the preparation of score roles rose to the level of his exacting professionalism. So they were having lots of fun but taking that fun very seriously. Burr is still alive and I've had many conversations with him. He's had some tough luck though, not only cancer, but also losing his home in the Paradise, CA fires. At some point I acquired three or four boxes of Humphrey's papers, so between my oral histories and Humphrey's diaries and clippings, I have a reasonable picture of his life and thoughts. COVID interrupted my research, but I was finally able to get his friend Robert Withers to deliver Humphrey's personal audiotapes to a transcription service, and while that took forever, and when they finally finished I was busy teaching, I'll finally be getting down to do some serious listening now.

I was happy to hear about Burr Van Nostrand, as I had written a short article years ago about a big revival of his works at NEC but otherwise hadn't thought about him in a while. Van Nostrand was one of the most colorful composers in Boston in his day, so to see one of his confederates also get the resurrection treatment is delightful. It seems that if there are contemporary players for Van Nostrand, there's hope for Evans, and any performance of the works I'd seen is bound to be a must-see event.

Below is my correspondence interview with Feldman, with Feldman's responses in italics.

+

A 1968 WGBH program introduced Evans with the phrase "Evans has been accused of creating 'freaked out' sound instead of music." You yourself described his contribution to Mosko's Outer's Covering series as "humorous and also trippy", and I can recall some pieces from the time that could fit all these descriptors on the surface. You arrived to the new music scene too late to observe any of Cage's happenings, or the Yale Bad Boys events, but in your opinion does Evans's music really fit into that whole atmosphere, or was he just writing experimentally in similar veins?

The answer will depend upon what you mean by "Evan's music." He left not only music, but stage works too, and these seem more like happenings than like (what people usually mean by) "plays" (I think they're "out there" even by the standards of theater of the absurd). One could easily take these stage works as "pieces," so as works of music in some reasonably extended sense. I think Humphrey would have made a joke out the question "is it music or not?" So there's a continuum of activity, from those Yale Bad Boy events, to his written happenings (whether they were ever realized or not), to his more obviously musical manuscripts, to his very most unconventional manuscripts. In the end, I suppose that the key difference between a work of music and a happening rests on that hardness of edge between the audience and the performers. I suspect that that was always in play for Humphrey, though I can't think of a statement in his own words that would clarify that especially. But I don't think, past a certain time, that he was ever merely "writing experimentally" in the sense he conceived his works primarily as the sort of sonic objects that audio recording can serve well. In other words I don't think he ever bought into the teleology that the purpose of a musical performance was only the making of specified sounds. I think it's important to say that he didn't feel he had to choose sides in the new music wars. I think Boulez and Babbitt were as important to him as Cage, and he took rock just as seriously. But it seems to me that nothing was merely an aspirational model for him. As soon as he "got something" he needed to assimilate it and also attempt to exceed it. Despite the hippy vibe, he was very competitive.

Graphically adventurous scores, especially hand-engraved ones, were all the rage then, starting in Europe but catching on big with the younger university composers. Berio and other international names certainly set the scene, but I suspect Crumb winning a Pulitzer for Echoes of Time and the River really cinched it. It seems to have faded after the 1970s, what with the simultaneous cooling-off of the Avant-Garde boom of the '60s and '70s, the rise of Neo-Romanticism, and the shift away from publishing hand-engraved scores. Is there a way to know if Evans would have put the work into that sort of music typography if he weren't entrenched in the times?

I think there's a lot to unpack here. During the 60's there was a gulf generally separating the traditional classical music world and the contemporary music world (I'm using what I remember as the term of art of the day; later people would speak of new music, experimental music, and lately contemporary classical music). Orchestras and recitalists simply programmed very little music by living composers, and most works of contemporary music got performed by specialists on concerts solely devoted to such music. Traditional classically-trained musicians not only had not taste for innovations even as mild as atonality, but they also had a great deal of concern for their personal dignity and even the dignity of their instruments (which meant that extended techniques were a deal-breaker). Conservatory students, and even more so, conservatory-bound students, concentrated nearly solely on common-practice works, the only music that mattered for their intended careers (and the only music their teachers could help them learn anyway). Meanwhile universities were the important employers and for contemporary composers, but universities demanded that tenure track faculty do "research." Merely well-crafted compositions in received styles did not count as research then. To make room for more conservative composers meant putting the question to role of composers in the academy writ large. So this affected hiring and tenure decisions as well as the treatment of students. Now my point is that something had to give. At some point classical music started to look like a dying art, even to its own conservative audience. Conductors and recitialists felt pressure not to cut out the living entirely. Auditions requirements started to include a "modern" work. The skill sets taught in conservatories slowly expanded. So at some point that gulf started to shrink, but the new connections involved compromise on both sides. Highly skilled players showed a willingness to take up new works and thereby expose them to a mainstream audience, but they generally wanted pieces that didn't push the envelope too hard. This was quite opposite the demands of new music specialist who did want to show off unique skills and to play works that would attract as much attention as possible for their unique character. Anyway, not pushing the envelope too hard not only meant conservative sounds and conservative techniques, but also a relatively straight-forward path to mastery. Players favored scores in traditional notation, and indeed perfectly professional traditional notation. Most didn't have time to read complicated "rule books" and learn extended notations, nor did they care to improvise or deal with graphic notations. (Of course the gulf has continued to shrink, extended techniques have become more standard, but most players still want scores that tell them clearly what to do.) So back to Evans. Evans learned manuscript preparation for Martino who learned it from Dallapiccola. Mosko too, and Mosko passed the skills to his students at CalArts. In fact, Zappa liked to hire Mosko's students as copyists, because if one hire would flake out, the next one could pick up at the next bar and no one would ever see the difference. It was Martino's deal with Evans and Lucky that he didn't mind how weird the music was, provided the scores were prepared magnificently. Thus I believe he "put in the work" as you say simultaneously as an act of conformity and nonconformity. I wouldn't compare Evans to Crumb so much as to Feldman and perhaps Haubenstock-Ramati. Crumb's scores are straightforward to play. In fact he told me himself that he used the circular staves and the like to force players to memorize the music. Feldman was putting players in new situations and Haubenstock-Ramati was making work that simultaneously lived in the visual art world. Humphrey never met an artform he didn't like, and though he was a composer first, he left fiction, poetry, visual art and he made films (presumably lost though). But you're asking me to predict a future that never happened. He died before the personal computer age, so I can't even guess what he would have done in an age where Finale and Sibelius became standards (and those platforms certainly don't easily support notational eccentricity). If famous players eventually had taken an interest in his work with the implicit requirement that the scores have a standard format, I'd guess he'd happily meet those commissions. I'm not aware that he ever received a commission. In fact, I don't think he had any idea where he fit in anymore once he left CalArts and academia and came to New York. Some of his friends feel that the resulting disconnect lead to his alcoholism and that eventually killed him. He was definitely struggling to find a new way forward, and talks about it in some of his letters, and there's a partial manuscript but as best I can tell, he never brought himself to finish it. I think it could have become a landmark in the history of LGBT+ new music.

Were the scores easy to photograph? My experience with the hand-engraved scores, especially manuscripts and self-published works, is that they can be difficult to read and even more difficult to scan or photograph. Consider how unreadable a Christian Wolff score can be with 50 years of yellowing and staining. The ones you've posted and sent me look quite pristine; did you clean them up, or did they just look that good?

They looked pretty good to start with and I did some cleaning up. Mostly I was photographing original manuscripts, so they were on those translucent onion skin paper with jet-black rapidograph ink. Harvard would not let me scan anything, so I used camera batteries as weights in order to get everything to lie flat, and I brought some solar desk lamps to provide uniform illumination. In some cases I wasn't happy with the focus, so I ordered the material out of storage for a second round, and brought my laptop to check the quality on-site. But I did use the computer to rotate pages slightly in order to make the staves perfectly horizontal, and that sort of thing. I also edited out any distracting artifacts. Some of the materials had some color, so I tweaked the colors until the results looked to me the way I remembered the originals.

Back in December, you posted in the Facebook group that you had finished transferring Evans's tapes into .wav files - is there a plan to release performance recordings? And will the surviving scores be collected for more public perusal?

It appears that more survive than you currently possess, but that doesn't mean they are accessible to you or others. I must confess that I haven't begun to go through all the files in earnest. Still, the basic answer is yes, in time I will release everything I have to the public. But the more nuanced answer is that I feel I need to be careful initially about the sound files. They're generally live performances, not by professionals, the sound captured without the benefit of excellent equipment or professional engineering, and the tapes generally 50 years old on top of all that. Experience has taught me not to expect anyone ever to bring imagination to their listening. People always hear exactly what they hear, so even a little 60-cycle hum or tape hiss turns into a deal breaker. Thus I don't want to release any sound that might hurt Evans' reputation and I have hours of repeated listening to do in order to determine the best use for each track. If and once I manage to get people interested, at that point there will be no harm in distributing it all.

Your comment that Evans may have written more for specific performers rather than for instruments, in a way that any stranger could theoretically perform it, is intriguing in both positive and negative ways. Classical composers can be led to worry quite a bit about the utility and longevity of their works - it's one reason I've never considered writing electronics into my music, as the technology can become obsolete quickly, even unusable. People also fade, and intentions can't always be easy to transmit in written or engraved instructions. Personal collaborations can be brilliant, of course - one wonders if Berio would have written a fraction of his groundbreaking vocal music if he'd never worked with Cathy Biberian - but unless a composer cares about making their intentions clear through scores, it's hard to know if any performance is true to their vision. Your comment about "ironic and paradoxical quandaries" brings back memories of performing from Cage's Song Book and big group works like Michael Finnissy's Vigany's Cabinet, where instrumentalists are left to interpret extramusical non sequiturs. You defended his music as requiring more personal engagement from performers without loosening the pieces enough that they fall apart, but how receptive do you think today's classical musicians are to that kind of challenge?

I didn't mean to suggest that Evans wrote for specific performers. I was trying to express a more theoretical pivot. A typical way of thinking about music centers everything around sound. In particular, when a human being plays an instrument, the "music" comes from the instrument. This does not mean necessarily that the instrumentalist effectively disappears. Audiences, even classical music audiences, will connect with the human presence. If the music seems to "express" something, perhaps listeners like to feel, or believe, that that something starts out inside the human performer, and gets out through the instrument. Now I'm sure standards of decorum have varied over time and from place to place, but in my experience, a classical performer may receive admiration for their deep concentration (which might be understood then to help the listeners concentrate) or their general grace, but performers also routine receive criticism for "too much body English" that suppose distract us from the music or seems meant to compensate visually for a lack of expression in the sound. I don't think it's much of an exaggeration to say that nobody thinks this way about rock, say, or even jazz. Those audiences expect, or at least welcome, a total performance. Now total performance suggests sound plus a theatrical element. And yes, composers have been experimenting with "theater pieces" for years. And one could have a whole conversation about the boundary between "theater with music" and "music with theater." But Evans viewpoint wasn't about adding theatrical elements to musical compositions. It was more, I think, about creating music that was fueled by the personalities of the performers, whomever they happened to be and whatever their personalities, rather then merely asking for a bit a grace and playing on the expectation (myth?) that whatever comes out (genuinely) started out on the inside. Of course theater generally involves actors playing roles, thus following a script and projecting feelings and emotions of a character. Those "theater pieces" essentially ask instrumentalists and singers too to play scripted roles. But Evans was interested in something else. I think he would be sympathetic to the notion that the purpose of a art is self-discovery. In particular, when we truly open up ourselves to a work of art, we learn things about ourselves. So he wanted his pieces to be vehicles for self-discovery even for, or firstly for, the performers. Whoever you are, you could become more yourself by playing one of his pieces, and you could and bring your whole self to the stage. Thus an Evans piece will be an interaction of actual personalities and much as an interaction of sounds. Maybe its an idea so obvious in jazz and rock that no one would need to spell it out, but it's still not typical or characteristic of classical music even 50 years after Evans' work. I should round this out by noting that while the '60s were a time of great experimentation and lowered inhibitions, there were also a time keenly aware of repression, continuing inhibitions, conformity and convention. Evans was a gay man and gay men were typically in the closet, or even so out of touch with their desires that, buried, they became a locus of inner conflict and frustration. Traditional classical music demands all kinds of conformity, to the tuning, to the tempo, to the style. Of course experimental composers were de facto non-conformists in their roles as composer, but often they still required performers to conforms themselves to the demands of the non-conformist score. Even with a score like Earle Brown's December 1952, in my experience musicians can be very judgmental about how far you can go, and specifically how far you can go lest the performance becomes more about you than about Brown's piece. Evans aimed to make pieces that would work because you made them about you, because he was fascinated by people and their interactions, and art seemed to offer the possibility of giving people the opportunity to be more themselves than they realized possible.

For decades, we've been in an era of resurrecting forgotten composers from the past - whole record labels exist for this sole purpose. However, the hard modernists of Evans's generation have mostly been passed over, perhaps because their music isn't quite old enough to be considered unjustly neglected, or perhaps because the music community just doesn't have any interest in that type of modernism any more. It's one thing to preserve scores and recordings, but another thing to spur on contemporary performances, which is where real change takes place. Do you think there are enough musicians interested in mounting works like Evans's, and his contemporaries, to hope for a wider revival?

History is not simply the past, but rather all the stories we tell about the past to make it legible and also useful to our present purposes. I believe that this logically gives rise to a phenomenon that you might call the historical uncanny valley. Some things are both too recent and not recent enough to be easily made legible; some things linger on the border between relevant and irrelevant (and even embarrassing), so we don't yet know how to use them to define ourselves and our current goals. In particular, we don't know what we should be citing as precedent and what we should be reacting against. Norman Rockwell is a nice example of an artist whose legacy suffered a historical uncanny valley. There was a time where it would have been inconceivable for an art museum to hang him; it would be like they were surrendering to their enemies. But ultimately the work aged to the point were curators could say to themselves that Rockwell's canvases help tell the full story of a time only partially documented (artwise) by works of the usual suspects. I hear a lot of work by composers, some with big careers, who are still working very much in the modernist vein. If I'm hearing a piece by, say, Liza Lim, and someone asks me what makes it 21st century music and not music from 1970, there first thing I would say is, if I could bring this work via time machine to a contemporary music audience of 1970, they wouldn't be shocked by it, certainly not the way an 1870 audience would have been shocked to hear Webern. Sure, there's been some evolution in taste, judgement and norms, but no wholesale rejection of the modernist aesthetic. But my point is that the very viability of our ongoing modernisms make those old modernisms tricky to frame. The old work is still competition for the new and its not clear what comparisons and contrasts to draw usefully. And dead composers can't do you favors if you play their work, and in many cases you can't even say "premiere." But time will pass, and at some point the classical music world (if it survives) will ask what was really happening during the 1960s and 1970s. That was an age when reputations got made by LPs, and so their were very few composers whose whole oeuvre was available for the listening public. It was one or two names from each European country: Germany-Stockhausen, France-Boulez, Poland-Penderecki, Hungary-Ligeti, Italy-Berio, Greece-Xenakis, England-Peter Maxwell Davies...and I'll add Japan-Takemitsu. It seems to me that those names are still dominating conversations (on the internet say) about the period today. Of course it's tautological that receiving the exposure they did, in their own time, has made these figures particularly influential. But we're going to find a lot of other very interesting work, and a lot of other fine work, when we dig. Many composers were unlucky, or just not good at self-promotion, or they were a little too radical or little too conservative then in ways that wouldn't matter to us now. So my answer is, yes, I'm hoping for a revival. I don't know when. Evans has a very colorful life - only son of CIA agents (I think), childhood homeschooled in India, one of the Yale Bad Boys, and then working for the notorious publisher Maurice Girodius and writing his own gay porn as a day-gig, and finally discovering (and essentially rewriting) V.C.Andrews Flowers in the Attic, one of the top-selling novels of all time. He's an interesting guy and he wrote interesting music, and I think his life has something to say about gay history and perhaps the impact of AIDS on the arts (He died literally one day before AIDS was defined by the CDC and became a thing. I'm not sure he had HIV, or if he did that that's what killed him, and I don't have access to his death certificate not that that would help, but many of his friends believe he died of AIDS). Some people might say "what does being gay have to do with the music?" but in Evans' case, I would say, a great deal. He was unconflicted about his sexual orientation, but definitely aware that not everyone enjoyed his freedom, and his music is really about freedom.

I believe that most serious artists have one or two Evans's squirreled away in their mental repertoire, artists who they believe are unjustly neglected, and that they feel like one of the only people on Earth who really know their work. In my time doing this sort of research I've known a few composers who ended up being the sole protectors, or at least sole promoters of the works of a deceased, forgotten composer, and I myself may be that for one or two names. If you fit this role for Evans, do you feel a responsibility to keep your work going, not knowing if anyone will continue it after you're gone?

My plan has been to write a book, part biography, part musicology. I've done dozen of interviews and I have had access to really an amazing about of primary sources. But it's challenging work. It can be very hard to figure out what's going on in a composer's mind from his messy personal notes and sketches. Robert Morris taught Evans the advanced serial theory of the day, and Babbitt was interested in teaching him at Juilliard, but it never worked out. While it's not surprising now to find composers who see the importance both of, say, Babbitt and Cage, but I think it was unusual back in that day to aim to synthesize such disparate, even diametric, influences. My point is that makes Evans' scores both interesting and challenging for a musicologist or a theorist, because you typically don't bring the same methodological tools to bear on such different composers. But I'm not sure that I'd call Evans "unjustly neglected." No one is guilty of neglecting him, rather, he simply disappeared. Dying young was part of it, but long before that he withdrew from the contemporary classical music world, perhaps on account of depression or simple writer's block or despair at figuring out where he fit in. If anything, rather than neglect, he may been the victim of too much early success: all those BMI prizes, orchestras playing his music when he was still in college, Tanglewood, people writing about him, putting him on television, etc. So I feel deeply in my gut that his disappearance has something to say about the sociology and culture of the classical music world and the contemporary classical music world. I'm still meditating over exactly what though. So yes, I do want to rescue those scores from those western Massachusetts archive boxes where they just sit silently almost all the time. Already some of the people I'd have wanted to talk to about Evans have passed away. It's clear that my carpe diem has saved the fabric of his life from falling down what we now call the memory hole. But it was speculative for me. Evans was described to me in the 1970s, by Robert Morris, as someone from whom I should expect great things. But there was nothing to hear and almost nothing to see. So his scores, sure, I want float them out to the world and give them the chance to sink or swim. But I also simply find his whole story compelling. I have the odd feeling that I've made friends with the man albeit decades after his death. And yes, that he's counting on me. And maybe it's a kind of "paying it forward," as I'm a composer myself. And neglected (justly or unjustly, not for me to say).

I extend great thanks to David Victor Feldman for taking the time to answer my questions and further promote Evans and his music, and hope the Society grows its collection and reach. In the meantime, I'll keep looking for fellow travelers who are willing to put in the time and effort to bring composers back from oblivion, and hopefully more interviews are on their way.

~PNK