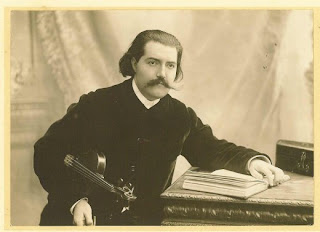

One of the most hazardous variables in the life of a musician, one that is rarely considered in a full appraisal of an artist's life, is the role of the artist's family. The question is not only how much they supported the artist's development, but also applies to how their work is treated after their death. A particularly sad case I came across is Thomas Peterson, an absolutely obscure Seattle composer who went unannounced through his whole life and quietly passed away in 2006. I found a few works of his on Dartmouth professor Larry Polansky's website, and Polansky led me to Peterson's old friend David Mahler. Mahler told me that the only kin who came in contact with Peterson's works after his death was his sister, who didn't understand the value of the work, and threw the majority of it out with the trash. Part of this included his unique quarter-tone counterpoint system, developed by detuning a chintzy Casio keyboard and playing it alongside a normally tuned one. I can't begin to tell you how heartbreaking that is, especially because of how rare successfully self-taught composers are - Meyer Kupferman's career consistency is doubly inspiring in light of this statistic. This brings us to Lucien Durosoir (1878-1955), a virtuoso violinist who taught himself composition, making little to no effort to show his work to the world. If it wasn't for the discovery of his manuscripts by his son, Durosoir's work may have been stuffed into the dustbin of history, and France would have been deprived of one of its most fascinating auto-didactic Classical oeuvres.

Entering the Paris Conservatoire at age 14, Durosoir enjoyed great success as a soloist, distinguishing himself with Parisian premieres of important late-Romantic violin concertos by Brahms, Strauss and Gade. He worked as a stretcher-carrier in the first World War, and during his duties became increasingly drawn to composition, collecting any and all scores that took his fancy. In 1921 he was offered the first violin chair of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but was involved in an accident before he could accept the post and was forced to give up playing the violin entirely. His retirement separated him from Parisian artistic circles, and his dormant compositional aspirations took flight. Receiving virtually no input from contemporary figures and trends, he developed a rich personal voice, aware of his time but pointing towards the internal timelessness of his own psyche.

His Trio avec piano, one of his most extended and representative works, shows off his penchant for unique harmonic textures and extreme drama right off the bat. A hypnotic piano motive anchors the listener as the strings swoon and melt into exotic outer harmonies, often employing harmonics and different bowing techniques to heighten the otherworldly air. There are times when Durosoir can't keep his imagination still, employing so many contrasting textural and harmonic ideas at once that the piece feels ready to collapse under its own weight (à la Jean Huré's Piano Quintet). He had that lovely ability to introduce recurring ideas in the middle of a seemingly rhapsodic section only to pull them out of his hat later on to create long-form cohesion, and even when the Trio seems to slip into noodling a familiar ornament or color surfaces. Despite this I wouldn't recommend Durosoir's music for those looking for a half-hour of incessant thematic pounding à la Franck's Symphony in D Minor*, as the arc trajectory of the Trio is more akin to a mountain range or the life cycle of a phoenix, a series of rhapsodic episodes linked by reiterations the mesmeric opening section - until the halfway point (13' 50''). Even the yearning adagio of the second movement can't fully control the tendril-like movements of the strings, and one can't help but think of the sight underneath a carpet of lily-pads, their vines tangling organically in the dark. One also can't help but read the video's description and see the uploader's description of the movement - "a piercing sadness from another time." I'll admit that Durosoir's harmonies occasionally seem a bit "I wrote this down but didn't actually listen to it", a tad sour for the rest of the piece, though I also get the feeling that the performers of the Trio didn't quite understand the piece as a whole. These attributes are entirely understandable when you consider that Durosoir had little-to-no performance opportunities for his work, composing merely for himself. The last "movement" is the most volatile of the bunch, ornaments and spare notes leaping from the fold without warning and harmonies at their most unpredictable. However, shades of the opening phase in under different cloaks, and the movement winds down for a bit before erupting in the final seconds.

It may be a while before the music world fully understand's Durosoir's music, as is the case with isolated artistic passions. His works are certainly concert-worthy and don't require ludicrous instrumentation or degrees in parapsychology, but there are those moments which aren't entirely, shall we say, "provable". However, those quixotic wrinkles are not only valuable to his artistic M.O. but also in the spirit of Debussy's dream of a lush musical world unconstrained by traditional notions of organicism and apartment-complex top-to-bottom order. His pieces reflect a wild internal world that can't be pruned to fit a front lawn, one far more reminiscent of the winding roots of an ancient forest, paths down which only shadows can travel. That being said, there's always room for simplicity, and among his works his Berceuse for cello and piano makes a calm and gentle end to a program of dense abandon, featuring one of his most poignant melodies. Once again, real beauty has no need to explain itself, and Durosoir's sui generis oeuvre has enough mystery and sincerity to endure on its own energies. Here's to another rock overturned, revealing rich soils and the untrimmed growth they bear.

It may be a while before the music world fully understand's Durosoir's music, as is the case with isolated artistic passions. His works are certainly concert-worthy and don't require ludicrous instrumentation or degrees in parapsychology, but there are those moments which aren't entirely, shall we say, "provable". However, those quixotic wrinkles are not only valuable to his artistic M.O. but also in the spirit of Debussy's dream of a lush musical world unconstrained by traditional notions of organicism and apartment-complex top-to-bottom order. His pieces reflect a wild internal world that can't be pruned to fit a front lawn, one far more reminiscent of the winding roots of an ancient forest, paths down which only shadows can travel. That being said, there's always room for simplicity, and among his works his Berceuse for cello and piano makes a calm and gentle end to a program of dense abandon, featuring one of his most poignant melodies. Once again, real beauty has no need to explain itself, and Durosoir's sui generis oeuvre has enough mystery and sincerity to endure on its own energies. Here's to another rock overturned, revealing rich soils and the untrimmed growth they bear.

~PNK

*If pressed to describe the Franck Symphony in a word I can't imagine a better candidate than "gooey". A lot of orchestra subscriber headaches might be fixed by simply replacing all instances of Franck's over-insistent ode to textural opaqueness with Paul Dukas's much fresher (and far less performed) Symphony in C.